Da Vinci has his Mona Lisa, Otto Wagner has his…well, many buildings in Vienna might be considered a highlight of the architect’s legacy. But the Postsparkasse building perhaps marks a turning point in modern architecture.

- Notable marble and aluminium façade

- Opened in 1906 with further expansion completed in 1912

- Perfect combination of aesthetics and utility

- Began as home to the state savings bank

- Now houses academic institutions (you can go inside)

- Book a themed guided tour* of Vienna

- See also:

Postal Savings Bank building

(View from the front)

One of the more unique buildings in Vienna bears the name Österreichische Postsparkasse, which translates directly to the Austrian Postal Savings Bank.

This turns out to be a remarkably accurate description of the building’s original occupants. Though back at the time of construction, the institution was the “imperial and royal” version.

The Postsparkasse’s fame stems from the its role as a standout example of architecture from the era of Viennese Modernism, as a toned-down child of Viennese Jugendstil, and as a product of the great architect, Otto Wagner.

Wagner was chosen from among the 37 architects striving for the design contract. Construction work began on July 12, 1904 and the bank’s new premises opened in December 1906 (with additions in a second building phase that lasted from 1910-1912).

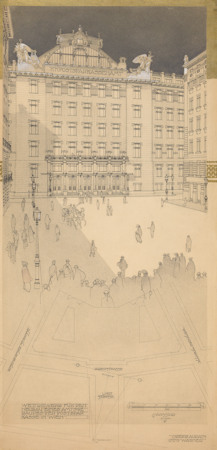

(Architectural drawings of the Postsparkasse as conceived by Otto Wagner for the competitive bidding process in 1903; Wien Museum Inv.-Nr. 96017/34; excerpt reproduced with permission under the terms of the CC0 licence)

The architect’s creative hand guided all parts of the building, even down to the fittings and furniture. You can find some of the latter on display in the Vienna Furniture Museum.

On the outside, marble plates and decorative aluminium rivets create the rather apt impression of a lockbox.

(Wagner also combined marble and rivets in another famous design: the Kirche am Steinhof church.)

The combination of materials used – notably aluminium, marble, glass and iron – would last “14 days longer than eternity” according to Wagner, as quoted in a contemporary newspaper article.

Die Zeit described the Postsparkasse as a work of genius, noting that Wagner wanted to produce a building that was:

…a symphony in white, black, and grey, but particularly one guided by expediency. Light, air and intelligent use of space…everything that was missing from the old premises should be here in abundance.

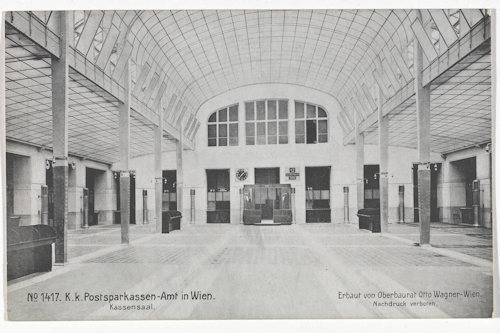

Inside, for example, a huge atrium-like hall with glass floor makes the best use of natural light:

(The Kassensaal of the K.k. Postsparkassen-Amt in 1907; Wien Museum Inv.-Nr. 215266/6; excerpt reproduced with permission under the terms of the CC0 licence)

As such, the Savings Bank represented Wagner’s desire to combine aesthetics with practicality: a core tenet of his modernist approach. As the Deutsches Volksblatt reporter wrote after a tour prior to the official opening:

The total impression given by the building must simply be described as beautiful and harmonious. Wagner has rarely managed to combine material and architectonics, stylish decoration (right down to the fine detail) and eminent fitness for purpose in such an excellent way.

The small (and free) Wagner:Werk museum inside the building used to tell the story of the Postsparkasse, the architectural competition, and the groundbreaking nature of the winning design. But I’m not sure if it’s still there.

The impact of that design is best exemplified by standing at the entrance and looking back across Stubenring to the government buildings opposite.

This new location for the imperial Ministry of War went up at about the same time as the Postsparkasse (Wagner even bid – unsuccessfully – on the project).

The ministry’s design still clung largely to old-style architectural approaches that followed the principles of historicism. The contrast is quite remarkable. You can picture eyes widening at the view of the PSK building at the time of its opening.

(Rooftop statue)

The Savings Bank continued as bank offices with service counters for most of its history. It now provides a home for academic institutions from the likes of the University of Applied Arts Vienna.

This academic repurposing has the rather fortunate side effect that you can go inside.

Carry on straight up from the entrance to enter the Grosse Kassenhalle (main counter space), for example, which looks like it teleported straight out of 1906. Back in the day, the Viennese must have felt like they had stepped into the future.

The Kassenhalle has a small self-service café within. The chairs slip neatly into the bentwood tradition, while mirrored tabletops create the kind of images that attract a multitude of likes on Instagram.

With everything seemingly as it once was, your imagination begins to fill with bewhiskered gentlemen and long-skirted ladies. Close your eyes to hear the staccato of ink stamps on paper and the constant scratching of fountain pens across a thousand slips of paper.

How to get to the PSK building

Although in the old town, the building sits off to one side of the traditional tourist areas.

Subway: a short walk from Schwedenplatz (U1 and U4) and Stubentor (U3).

Tram/bus: the tram lines 1 and 2 both stop at Schwedenplatz and the nearby Julius-Raab-Platz stop. The 2 also goes to Stubentor.

The monument you see as you face the front entrance from Stubenring road (next to the underground car park) is in honour of Georg Coch, the Postsparkasse’s founder and first director.

You’re not far, either, from some other lovely examples of Modernist or Jugendstil buildings. Fleischmarkt is but a block away and offers the Residenzpalast, the Meinlhaus, and other turn-of-the-century architectural joys: see here for details.

Fleischmarkt also has another attractive arrow in its quiver of buildings in the form of one of the better places to fill up on coffee and cake: Cottage Roasters in Diglas.

Address: Georg-Coch-Platz 2, 1010 Vienna